In my first post about collecting data from the talkbass classified forum, we discussed web scraping with PyQuery. We stored the collected information in a dictionary with certain specific keys that I promised to explain in a future post. Those specific choices will become clear in our discussion here where we’ll discuss the NoSQL database management system MongoDB.

“Mongo only pawn…in game of life.”

–Mongo, “Blazing Saddles”

Why MongoDB as opposed to an RDBMS?

Given the relative simplicity and wide adoption of the SQL standard, a relational database management system (RDBMS) would certainly be an appealing option for the purpose of storing the data we’ve scraped. Unfortunately, relational databases come with at least two shortcomings when it comes to storing the largely text-based data we’ve scraped from the talkbass classified forum.

The first issue is the fact that relational databases require the declaration of atomic data types in their schemas. This is particularly restrictive for text fields, for which we would need to determine ahead of time the number of characters allowed for each column. The disk space is then carved out using the same rigid character number for each row (or record) of the table. This can result in a lot of wasted space, especially when text-based fields can vary widely by length. In the talkbass data, the thread_title field is of particular concern.

In addition, a relational database enforces a rigid schema. This means that if we want to, for example, change the number of characters allowed in a text field, we have to effectively recreate the entire table on disk. If we tried to dynamically determine the number of characters allowed for the thread_title field, we’d need to change the schema each time we collected a new longest title. This would have a substantial effect on the speed of our data collection.

The document database MongoDB relaxes both of these restrictions. As of this writing, I still haven’t decided whether I want to store the original thread post, along with the information we’ve scraped from the thread link pages. With MongoDB, I don’t have to worry about changing the schema if I want to add some extra information. I also won’t have to worry about wasting a bunch of disk space if I only wish to collect a subset of the original posts to test the value of the information. MongoDB won’t hog disk space for threads for which I didn’t scrape the original posts.

Of course, there’s no such thing as a free lunch, and this flexibility comes at the cost of query speed. The rigid schema of an RDBMS speeds up the query engine because information is stored in well-defined, organized locations on the disk. This is not the case with MongoDB; I like to think of it like the difference between an array and a list.

Getting started with MongoDB

The MongoDB download page can be found here, and here is a solid tutorial to help you get familiar with how to set up and interact with MongoDB.

After installation, we can create data/mongodb/ in our working directory. Next, we need to establish a MongoDB connection by executing

mongod -dbpath data/mongodb/

from the command line. Once the connection has been established, we’re ready to start interacting with the database using Python.

Pymongo: Inserts

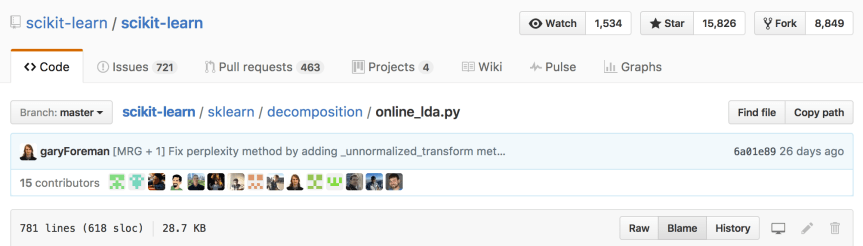

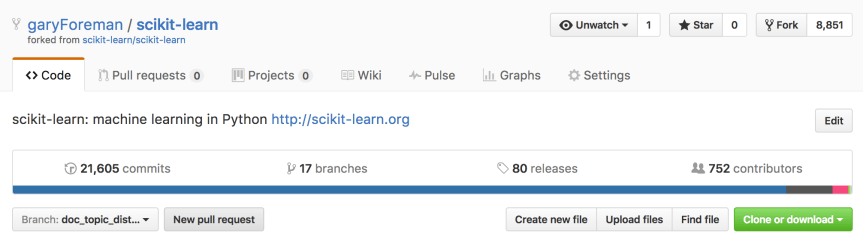

The full context of the code below can be found here, which is the same script that contains the code from my first post. Here, I’ll summarize the key lines of code that are responsible for interacting with MongoDB.

import pymongo

...

# Establish connection to MongoDB open on port 27017

client = pymongo.MongoClient()

# Access threads database

db = client.for_sale_bass_guitars

...

try:

_ = db.threads.insert_many(document_list, ordered=False)

except pymongo.errors.BulkWriteError:

# Will throw error if _id has already been used. Just want

# to skip these threads since data has already been written.

pass

...

client.close()

We import the pymongo package, and then we create a client that allows transactions with MongoDB through the connection we established by running mongod. Next, we tell the client to load the for_sale_bass_guitars database. If the database does not exist, it will be created automatically, otherwise, the existing database will be loaded. At this point, we’re ready to make insertions, deletions, and queries.

In the try block, the db.threads.insert_many() method allows us to insert multiple documents into the threads collection simultaneously. Think of a “collection” as a “table,” and just as for the for_sale_bass_guitars database, the threads collection will be created automatically if it does not already exist. In our example, document_list is a list of 30 dictionaries that contain the information we’ve scraped from each of the for-sale thread links on a single page of the talkbass classifieds. As a reminder, each document is a dictionary defined as follows:

self.data['_id'] = self._extract_thread_id() self.data['username'] = self._extract_username() self.data['thread_title'] = self._extract_thread_title() self.data['image_url'] = self._extract_image_url() self.data['post_date'] = self._extract_post_date()

MongoDB uses _id to indicate the unique key identifying each document. If this key is unspecified in the inserted document, MongoDB will automatically create it for us. Since talkbass has already assigned each thread a unique id, it would be redundant to allow MongoDB create a new identifier, so we set _id equal to the thread id value.

MongoDB guards against the insertion of multiple documents with the same _id, which is supposed to be a unique key, after all. By setting the ordered argument of the insert_many method to False, we insure all documents in document_list that are not present in the threads collection do get inserted before a potential exception is thrown based on an _id conflict. If ordered were set to True (the default behavior), no documents appearing after the first instance of a duplicate _id will be inserted, which is not the behavior we want in this case.

Finally, the except block gracefully handles the BulkWriteError thrown when an _id has been duplicated. This allows us to re-scrape the classified forum without having to worry that we’ve already seen some of the threads and committed them to our database. Then, once we’re done scraping, we close the client before exiting the Python script.

Pymongo: Queries

Once we’ve inserted documents into MongoDB, we need the ability to query them. Again, this requires a connection established by mongod before interaction via pymongo

import pymongo

...

# Establish connection to MongoDB open on port 27017

client = pymongo.MongoClient()

# Access threads database

db = client.for_sale_bass_guitars

# Get database documents

cursor = db.threads.find()

...

for document in cursor:

thumbnail_url = document[u'image_url']

...

client.close()

Just as before, we create a client and load the for_sale_bass_guitars database. Next, we call the find() method on our threads collection to create a generator that gives us access to our stored documents. Then we can create a loop using that generator to access the information we wish to collect. Note: because cursor is a generator and not a list, we can’t repeatedly access the first document of the threads collection using cursor[0]. If we wish to reload the first document, we need to rerun the find() method.

The context of the code above can be found here, where I use the stored image urls to scrape the bass image associated with each for-sale thread link. The scraping and preprocessing of these images will be the subject the next post in this series.